Transcript

Treatment targets in CIDP

Jeffrey Allen, MD

All transcripts are created from interview footage and directly reflect the content of the interview at the time. The content is that of the speakers and is not adjusted by Medthority.

So thinking about where the treatment space is right now, what's evidence-based, what do we use? We know that IVIG, subcutaneous IG, corticosteroids, plasma exchange and FcRn antagonists have some data support. They support their use. They all have their pros and cons in terms of how they're administrated. You know, IVIG and subcutaneous IG, of course, IV and subcu, steroids have the advantage of being oral or IV, plasma exchange is of course IV and then FcRn antagonists are subcutaneous. Their onset of action is quite variable for immunoglobulin products. At least IVIG probably takes several weeks to up to three months to show some effect, perhaps a little bit longer in some situations. Corticosteroids probably take a little bit longer. Plasma exchange, weeks to months is usually when we see an effect. So they've got their pros and cons in sort of the logistics of an administration. From a mechanistic standpoint, some of those have a broader mechanism of action and some of them have a more targeted mechanism of action. For immunoglobulins, we don't understand fully why they work in CIDP, but the proposed mechanisms are multiple, including competing with or blocking pathogenic antibodies, presumed pathogenic antibodies. There may be some evidence that it interferes with complement to some degree, although that seems to be a modest benefit at most. Corticosteroids, of course, have an anti-inflammatory mechanism of action.

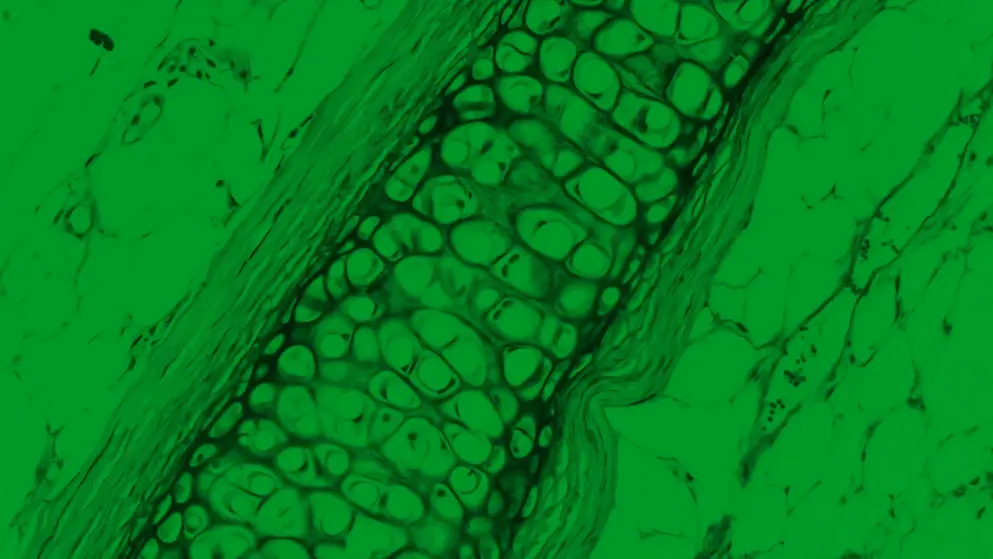

You know, plasma exchange removes pathogenic antibodies of a certain size, but there's probably other immune complexes that are removed with plasma exchange. And then an FcRn antagonist of course works through reducing IgG autoantibodies and IgG levels. So I won't review the pathobiology of CIDP in detail, but we know that it's multifactorial. There's many things at play. There's T-cell upregulation in the periphery. Antibody production, breakdown of blood nerve barrier, increasing in a pro-inflammatory state complement gets activated and upregulated, which increases binding of macrophage and autoantibodies. So different components of nerve and that can be very, very damaging. So if we know that those different things are at play, which of those mechanisms are potential targets for immune therapy? Should we go after the B cells and the antibody production, T-cell activation in the periphery?

You know, should we clear out those antibodies, you know, with an FcRn antagonist or should we go and block complement? And if so, which component of complement should we block? So reviewing a couple of these mechanisms in a bit more detail. So the FcRn antagonist. Yeah, so the FcRn is of of course, a really important receptor that lives in endothelial cells. And so, these are within the blood systems. So immunoglobulins and pathogenic IgG antibodies are flowing through the vasculature get taken up by the endothelial cell and then those IgGs make their way into the endosome, you know, where they'll try to bind the FcR receptor. If those antibodies and IgG immunoglobulins are lucky enough to bind that receptor, then it gets returned back into circulation. But there's only so many amount of seats at the table. There's only so many number of receptors. And so if immunoglobulins are not bound to the FcR receptor, they get signalled for destruction by the lysosome. So by blocking that receptor with an FcRn antagonist, you shunt more of those IgG and presumably IgG pathogenic antibodies to the lysosome for destruction.

So we know that the FcRn antagonist can drop the IgGs by roughly 70% in most cases. Another therapeutic approach that's often used is B-cell depletion, but by targeting CD20 and induces a macrophage or a complement-mediated binding to the B cells, which results in its destruction. And then if it is producing pathogenic antibodies and that's what's causing the disease, potentially that's where the therapeutic benefit might come from. From a complement standpoint, you know, we've heard about the complement pathway, so I won't rehash this in great detail, but we know there's different components to the complement pathway, the classical, the lectin, the alternative, and these are really cascading, amplifying end pathways. And so where you block this pathway is probably important and for what effect you might have. We can block it at the end, the terminal complex components and limit, you know, the formation of membrane attack complex. But they may not be the whole story. If we wanna do something meaningful, our disease could go back upstream, you know, and get those parts of the pathway that are important for optimization and also inflammation. So inflammation, increasing the vasculature, you know, vascular permeability and what that does for the disease.

But also this other side of it, this optimization part, which is really the part that complement that's gonna tag different parts of the whatever it's going after, in this case, peripheral nerve, tag them for destruction, you know, and that is also an important part of the complement pathway that we may need to mediate in order to really get our effect on it. So by going more upstream, going after C1 and C2, not just the terminal complement pathway, we potentially can not only stop the terminal complex components, but also you know, the inflammation and the optimization parts of the pathway as well. So a little bit more about the upstream complement blockage, the two targets you know, that really are, we're going after most often are the C2 and the C1 complex. And the C1 complex can go after C1q or C1s. So by getting to, again, to those upstream components of the complement pathway, we may be able to lessen inflammation. And also that tagging process, the optimization process, which is gonna help macrophage and other components bind to the nerve, which may ultimately result in spared axonal destruction, improved axonal integrity and that may have some important benefits in order to prevent, you know, disability and nerve damage. Claudia kind of highlighted some of the predictors of poor response and poor prognosis in CIDP and many of these are well known. One of them is axonal damage. The more axonal damage you have, potentially the more irreversible nerve failure you have.

And that's really where the long-term disability comes in 'cause that nerve doesn't grow back. So if we can spare that nerve damage, that axonal injury by early complement inhibition or by some other mechanism, we have that potential to improve the long-term outcome of patients that are treated. Of course, identifying those patients and treating early before that process really sets in is really an important component. Whether or not complement inhibition and early complement inhibition leads to, you know, less axonal injury and ultimately a better state of outcome is something I think we really need to pay attention to as for the trials grow out, and really to understand if the opportunity to intervene with complement gives us a more bigger opportunity to make patients better above what they're already getting for standard of care is another ongoing question. Of course, whenever we introduce new therapies, thinking about the, you know, safety profile is very important in the treatment logistics of those new therapies is important as well. So where are we going? Where's the future directions for CIDP management?

Well, identifying some of the subtypes that are driven based on immunobiologic characteristics is really, really important. Biomarkers comes into some of that, but knowing which patients are really going to benefit most from an FcRn antagonist or antibody depletion or a B-cell inhibitor or complement is really an ongoing question I think we'd all like an answer to. Another future direction is to understand the role of axonal integrity in the long term outcome of patients. It seems to be very important to lessen disability in the long term, but we'd like to know more about it. We'd like to know more about how to optimise CIDP management with fewer side effects, make it easier for patients to do to lower the, not just the disease burden, but also the treatment burden that patients need to endure in order to prevent their disease from worsening. We talked a little bit about consensus guidelines yesterday and trying to understand really what it means to be a responder or to relapse or to be in remission. All of these things are important to be on the same page about what that really means, both from a patient perspective and a clinician perspective and many other perspectives in clinical practise and in clinical trials.